Welcome! This project recently migrated onto Zooniverse’s new architecture. For details, see here.

Research

What is it?

Shark Spy is a citizen science project that collaborates with schools and communities to collect baseline data on New Zealand sharks using local knowledge and community sightings in tandem with scientific survey methods. The project aims to connect local community to their coastal environment while teaching and improving science skills. The data that is collected is made freely available for the use of community groups, schools, and iwi. It is a project co-ordinated by the University of Otago's Marine Studies Centre.

Why does it matter?

There is currently a lack of data pertaining to shark species that inhabit coastal ecosystems around New Zealand. Sharks play an important role as apex or meso-predators by shaping coastal food webs via top-down control and risk effects. New Zealand coasts are home to numersous species of shark including but not limited to:

- Great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias

- Porbeagle shark, Lamna nasus

- Mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus

- Blue shark, Prionace gluaca

- Bronze whaler, Carcharhinus brachyurus

- Thresher shark, Alopias vulpines

- Basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus

- School shark, Galeorhinus galeus

- Small-tooth sand tiger shark, Odontaspis ferox

- Rig shark, Mustelus lenticulatus

- Sevengill shark, Notorynchus cepedianus

- Spiny dogfish, Squalus acanthias

- Smooth hammerhead shark, Sphyrna zygaena

- Carpet shark, Cephaloscyllium isabellum

(Anderson et al., 1998; Roberts et al., 2008)

Unfortunately, the lack of basic demographic information on many species in New Zealand limits conservation, management and policy initiatives (Ford et al., 2018). The majority of data on sharks in New Zealand are collected by commercial fishing operations which on its own presents numerous biases (eg. unrandomized sampling, gear selectivity, reporting errors etc. Santana-Garcon et al., 2014). Smaller localised data collection is ideal to obtain detailed demographic pertaining to that area, and when used in tandem with fisheries data can present a more robust representation of the real world. Specific parameters that are sought include locality, species richness, abundance, sex ratio, and size.

How does this project help this?

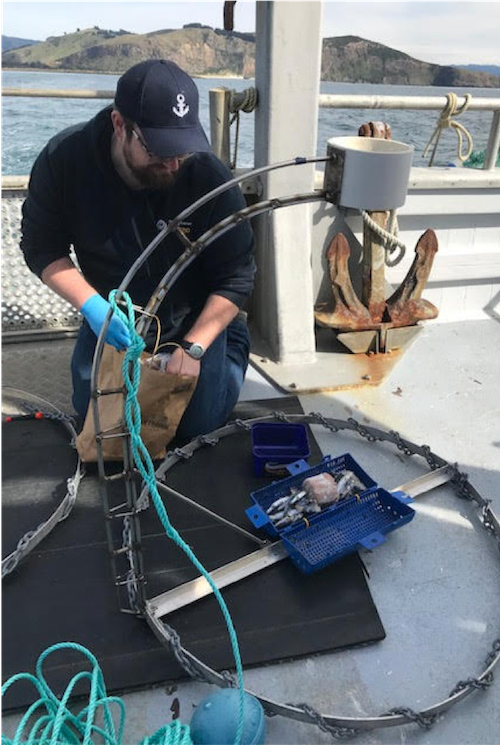

In this project you can help fill in some these gaps, specifically species richness and abundance. As mentioned above the way we do this is by using baited underwater video stations. Video is great as it is cheap to produce, it can be saved and reused for future projects, and its non-invasive to the animals that visit the station. While the presence of the baited station does present some biases, they are far more manageable than those of having a diver in the water, or physically catching and restraining the animals. In the image below you can see Rob filling a bait box with Pilchards (~250g) to attract the sharks. The bait box sits in the middle of the BUV frame (1m diameter) and it has a go-pro style camera that sits in the protective white cap above it.

The baited stations are left for an hour of recording, however in the analysis it is only the first half an hour of the video that gets analysed. The reason for this is that we want to count what is already in the area, rather than attract something in from further away. It also helps manage the bias of how far a bait plume may travel (on a windy day you're likely to get critters from further away for example). After the stations are retrieved the videos are downloaded and then split into frames. We chose to split each second of footage into two frames to allow for minor things to be caught, but also to limit the size of the sample sets. The result is something like the example below.

From here is where the data extraction comes in. From this video alone we can calculate a species richness (number of different species), a relative abundance (how many of a single species we can see in a single frame at a time), and we can get an estimate of size. Some species (e.g., sevengill sharks) can be individually identified using body markings (Lewis et al., 2021). Resighting a known individual further allows us to track where and when sharks may be moving to.

In all we hope that this data can be used in upcoming strategic meetings on the national plan of action for sharks in New Zealand. All sightings information is also forwarded onto iNaturalist (Shark Spy) so that the data and information is freely available for the use of schools, community groups, or interested parties.