FAQ

Why are you interested in material culture?

Historians have long been interested in the goods that people bought or otherwise obtained in the past, but mainly for what they can tell us about past economies - what goods were available, how much did they cost, how did costs relate to wages and so on. More recently, however, scholars have started to think more about the meaning of objects and how this changed over time. The period 1540-1790 was one of considerable economic change in England as trade and manufacturing expanded, new goods were increasingly available, and jobs and incomes were changing. We are interested in how these changes were experienced, as well as the economics of such developments. We will be exploring that topic by considering the type and volume of goods bequeathed, and the meanings attached to them.

Why are you using wills?

Most existing studies of material culture in this period have either used lists of objects owned (found in inventories and other sources) or have focused on objects that have survived. In both cases uncovering the meaning attached to such objects is difficult because neither source provides evidence of what the owners thought; instead, their opinions and feelings have to be imputed. Wills are different in that they often contain not just a record of the goods owned by the individual making the will, but also comments revealing their attitude towards the object or to the recipient. For some examples of these kind of comments please see our blog. Wills are particularly useful because they are the most common personal source that survives from this period. While wills skew towards the richer parts of English society, they nevertheless allow us to study a far larger fraction of the population than has previously been possible.

Why do you need to use Zooniverse?

The wills from this period vary in length and in the handwriting used, but in general they take between 30 minutes and an hour to read and process by hand. It is, therefore, difficult to work with them in large numbers without some kind of automation. Our project is using a Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model to automatically transcribe a large number of wills, 25,000 from five sample periods: 1538-52, 1604-08, 1664-6, 1725-6 and 1785-6. This model is trained on a set of transcriptions produced by experts in this period, and it can produce transcriptions very rapidly, but the outputs need to be checked before we can move onto analysis. The workflows on our Zooniverse project are designed to allow volunteers to check the accuracy of these automatically generated transcriptions as well as contributing their own transcriptions. Doing so will allow us to accurately transcribe a large sample of wills covering an important period of English and Welsh history.

**What is the difference between the Master and Apprentice workflows?

The images we have vary greatly in quality, some are easy to read but others, because they have faded or are very noisy, are quite difficult to transcribe from. Similarly, the handwriting across this period varies in difficulty, generally the earlier the will, the harder the handwriting is to read because it is increasingly different from modern hands. To help with this we have split all our images up by the quality of the image. The Apprentice workflows contain images that are easier to read, whereas the Master covers those images that we think are likely to be more challenging to read. Please have a go at either workflow and move between them as you become familiar with certain types of handwriting or want a new challenge.

It is important to note that the selection of which images are 'hard' and 'easy' has been done automatically, so some tricky ones may appear in the Apprentice workflows and some easy ones in the Master workflows.

Where can I get help reading the handwriting?

Wills from this period were written in a variety of different handwriting styles, some of which are drastically different from modern handwriting. Additionally, the images we have of these wills are quite low quality and so some letters or words will be difficult to read. There are plenty of online resources to help with reading historical handwriting, links to which can be found in our Field Guide. You can also find example alphabets and words from various periods in the Field Guide under Secretary Hand, Italic Hand and Common Words. If you are struggling with a word then approach it letter by letter, and if there is something you cannot read mark is as unclear or discuss it with the team and others on our talk boards.

Why are some of the images low quality?

The wills we are using are held at the UK National Archives in a series called PROB 11. These are wills that were proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. They were initially microfilmed in the 1950s by the Church of the Later-Day Saints and then again when the wills were moved from the Principal Probate Registry to the Public Record Office (forerunner of the National Archives). It is this second set of microfilms that were then scanned in the early 2000s so that they could be made available through the National Archives' website. Our images are, then, scans of microfilms of the original will registers. This is why some of them are low quality, with some very difficult to read. We have had a small number re-scanned to allow us to construct our ground truth data with which to train the HTR model discussed above. If you look at the Handwriting Training workflow, and move between the microfilm scans (the first image you are presented with) and the new high-quality scans (the second image obtained by pressing next underneath the image), you can see the substantial difference in quality and clarity of scan. Unfortunately, it is too expensive to rescan the entirety of the wills held in PROB 11 so we have to make do with the low-quality scans produced from the microfilms. We appreciate that this is not ideal, and that sometimes an image will be too difficult to read. We are filtering out the worst cases, but you are likely to come across some where the text cannot be read, in such cases feel free to refresh your browser and continue with another image, or indicate it to us by marking in unclear as noted in the instructions to each workflow.

Why are you not showing me the whole will?

In both the Checking Transcriptions and Transcribing Wills workflows we show you a section of a will, with a single line underlined. We do not show you the whole will, but we do give several lines either side of the line to be checked/transcribed. Hopefully these additional lines will provide some context and some additional examples of letters and words to help you decipher the text which that image is focused on. We only give you a relatively small section of each will in order to keep the task focused on that line, rather than requiring you to read through lots of other lines. If you cannot decipher something in a given line then do not worry. In both workflows you can mark a given word, section or whole line as unclear, rather than having to spend considerable time searching the rest of the page for a similar letter. Each line will be seen and processed by multiple users, thus, any problems with single letters, words or sections will be resolvable by comparing multiple responses from users and the research team. So, do not worry if you cannot decipher something, any attempt you make will be useful, and you can always refresh the page and move onto a different image if you would rather not submit a response to a case you are uncertain about. Additionally, wills have a formulaic structure, with similar phrases appearing in each will. As such, we do not need to check every line by hand, instead many can be automatically checked and corrected, allowing us to focus on, and show you, lines of particular interest to our project.

Why is part of the line of text cut off?/Why does the red line not extend to the whole line?

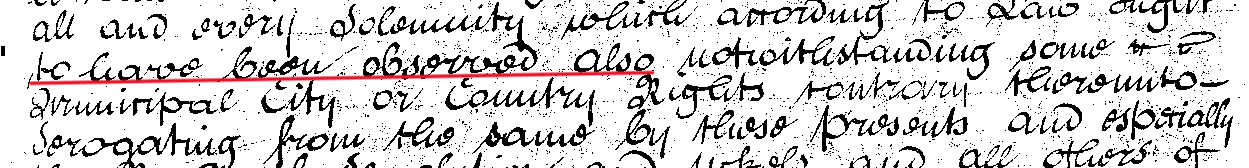

The red line that indicates which bit of the text to check or transcribe is generated by the HTR model. When we upload images to be transcribed by the model the first stage is perform what is called layout analysis. This is an automated process where by a model identifies all lines of text on a page. This layout is then used by the HTR model so that it knows which bit of the image contain text and should be transcribed, and which bit of the page is empty or otherwise irrelevant. The model to identify the lines has been trained on our ground truth and other material and does a good, but not perfect, job of identifying lines of text on the scanned wills. Sometimes the model splits one line into two sections, this is more likely to happen in cases where there is a word inserted or deleted from a line. In such cases it is important that you just transcribe/check the underlined part, rather than adding in the part which has been missed. We can knit the lines back together after we have correct transcriptions, but if words are added to the end of a line, this will cause repetitions in the final output. For example, in the image below a line has been split into two sections, as indicated by the fact the red line does not extend along the whole of the line of text. In this case you would just transcribe 'to have been observed also', and the rest would appear as a second image with the right-hand side underlined.

What will the project's outputs be?

The project will produce a range of different publications and outputs. The team will be writing several academic journal articles and editing a volume that will showcase the range of issues relating to early modern material culture that can be explored using the 25,000 wills. The transcriptions of the wills themselves will be freely available, as will the database of objects derived from the wills. These outputs will appear over the next few years, until then our blog will detail our progress, discussing interesting wills, our methods and other issues related to the project. We also have a mailing list where we update subscribers on our progress and outputs, please visit this site to sign up.